- Very careful analysis of all the facts surrounding incidents is imperative to avoid overreporting or underreporting HIPAA breaches.

- A breach of PHI must be reported unless there is a “Low Probability that the PHI is or will be compromised.”

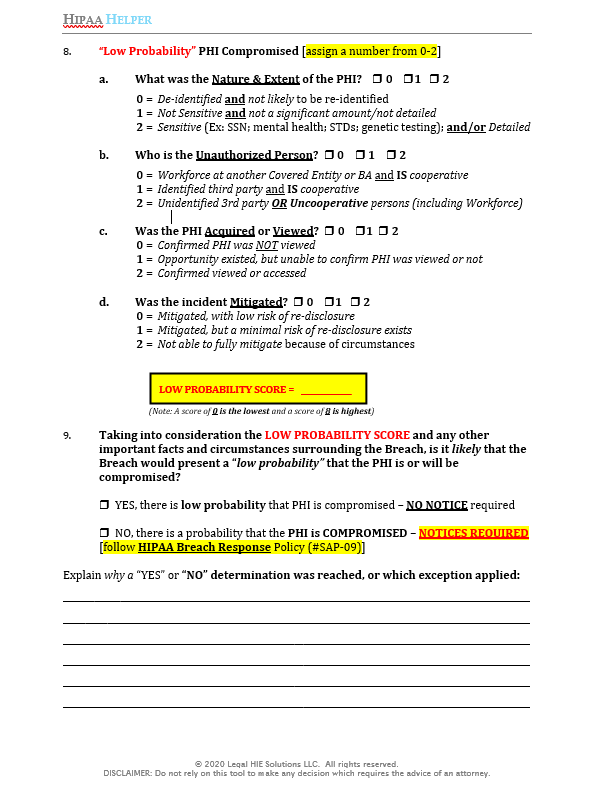

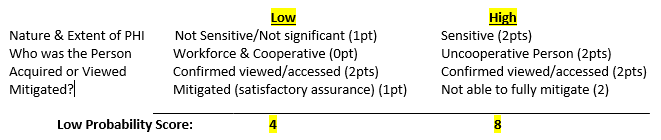

- A breach risk assessment requires evaluation of 4-Factors: (1) Nature/Extent of PHI; (2) the Unauthorized Person; (3) if the PHI was Acquired/Viewed; (4) Mitigation success.

Evaluating incidents that affect protected health information (PHI) to determine if they must be reported under HIPAA’s Breach Notification Rule is a delicate balancing act. On the one hand, a HIPAA covered entity will want to avoid reporting an incident to the Secretary of HHS if it is not required to do so under the standards set forth in HIPAA’s Breach Notification Rule. On the other hand, a HIPAA covered entity that fails to report a HIPAA Breach risks being exposed to penalties from OCR for each day such Breach was not reported when it should have been.

A recent Becker’s Health IT article brought attention to a Notice posted by Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago which explains that in March 2020, the hospital discovered that between November 1, 2018 and February 29, 2020 an employee “may have accessed certain medical records without a work-related reason.” The hospital also reported the incident to the Secretary of HHS which is posted on its Breach Portal and further reveales that over 4,824 patients’ electronic medical records were subject to “unauthorized access/disclosure” by the hospital employee. The hospital’s reporting of the incident will also result in OCR investigating the matter, as is noted on HHS’ website (i.e., “This page lists all breaches reported within the last 24 months that are currently under investigation by the Office of Civil Rights”). The hospital has since also been sued by the mother of a 3-year old child whose medical records were accessed by the hospital employee. That lawsuit is seeking class-action status to include other patients whose medical records were inappropriately accessed. Therefore, the stakes are high — and so covered entities should be aware and sensitive to the fact that reporting an incident to HHS that might actually not need to be reported under the standards set forth in HIPAA’s Breach Notification Rule could unnecessarily subject an organization to OCR’s review of not only the reported incident, but also its HIPAA compliance program in general. Additionally, notifying patients of incidents even when there is a “low probability that PHI has been compromised” could trigger unnecessary lawsuits.

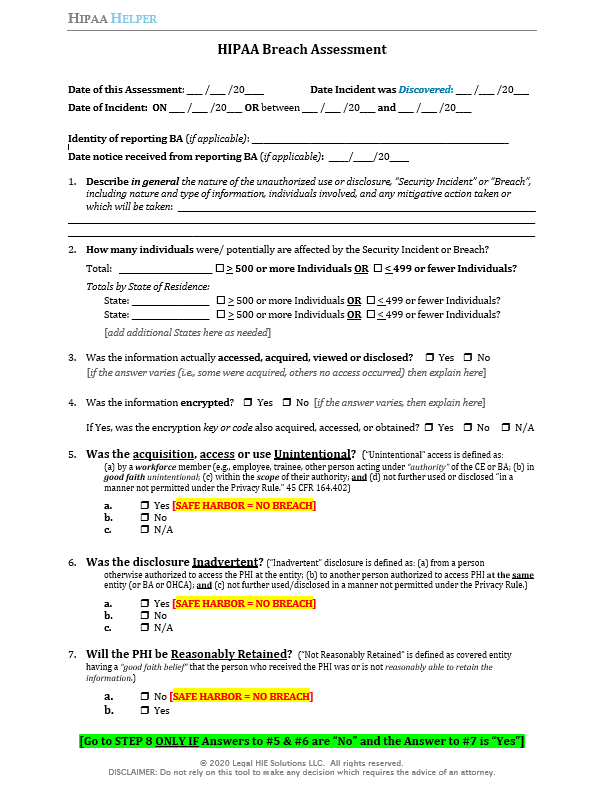

Evaluating incidents like the one experienced by Lurie Children’s Hospital is always fact-sensitive and hinges on collecting as much information as possible to complete a thorough and accurate HIPAA Breach risk assessment. A covered entity should also apply consistent methods to evaluate incidents and make determinations on whether breach reporting is required under HIPAA. The HIPAA Breach Assessment tool provided at the end of this article is one way a covered entity can attempt to standardize its approach to evaluating incidents and breaches under HIPAA. While such a tool should never be solely relied upon to reach a determination on how to respond to a potential HIPAA breach, it does introduce helpful structure and objectivity to what can otherwise be a precariously subjective and, at times, messy process. With that, let’s take a closer look at HIPAA’s specific standards and requirements for when a Breach must be reported.

When a covered entity discovers a breach of unsecured PHI, it must notify affected individuals, HHS and, in cases of breaches involving 500 or more residents of a single State, the media IF such PHI has been, or is reasonably believed by the covered entity to have been, accessed, acquired, used, or disclosed as a result of such breach. See 45 CFR 164.404(a); 164.406; & 164.408. A “breach” is specifically defined in the Breach Notification Rule to mean, and is limited to:

“the acquisition, access, use, or disclosure of [PHI] in a manner not permitted under [the Privacy Rule] which compromises the security or privacy of the [PHI].” See 45 C.F.R. 164.402.

Any acquisition, access, use, or disclosure of PHI in a manner not permitted under the Privacy Rule must be presumed to be a Breach UNLESS the covered entity can demonstrate that there is a “low probability that the PHI has been compromised” based on a risk assessment of at least the following factors:

- The Nature and Extent of the PHI involved, including the types of identifiers and the likelihood of re-identification;

- The Unauthorized Person who used the PHI or to whom the disclosure was made;

- Whether the PHI was actually Acquired or Viewed; and

- The extent to which the risk to the PHI has been Mitigated.

See 45 C.F.R. 164. 402(2).

A covered entity has the burden of demonstrating that the use or disclosure did not constitute a Breach as defined by the Breach Notification Rule. See 45 C.F.R. 164.414(b). The covered entity must also maintain documentation sufficient to meet this burden of proof for six (6) years. See 45 C.F.R. 164.530(j).

Therefore, every covered entity that is evaluating an incident involving the unauthorized acquisition, access, use or disclosure of PHI should analyze the 4-Factors to determine whether sufficient evidence exists to demonstrate that there is a low probability that the PHI has been compromised. Again, such analysis is inherently fact-sensitive and will require judgement. In its Description and Commentary to the Final HITECH Omnibus Rule published in January 2013, HHS offered additional guidance on how to evaluate each of the 4-Factors, which is reprinted at the end of this Article.

So, if the 4-Factor analysis is applied to a situation where an employee accessed patient records in an unauthorized manner, what might the outcome be? Using the scoring methodology in the HIPAA Breach Assessment tool, the following outcomes are possible:

outcomes are possible:

Thus, in a case where an employee accesses PHI that is not sensitive or significant (i.e., no social security numbers or financial information), is cooperative and the situation is fully mitigated (i.e., employee signs a confidentiality agreement, as HHS suggests would be a mitigating factor, and there is no evidence that the PHI was misused or publicly released), then a covered entity might be able to demonstrate that the documented evidence supports a finding that there would be a “low probability that the PHI was compromised.” On the other hand, if the information accessed was sensitive, the employee is uncooperative, and the covered entity is not able to fully mitigate the situation, then the presumption of a breach would likely stand and notifications and reporting to individuals and HHS would be necessary.

Without knowing the specific details surrounding the employee incident which took place at Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, it is impossible to know which specific factors might have tilted the hospital to decide to report their incident. However, covered entities faced with similar situations should undertake a careful analysis of their facts against the 4-Factors, together with HHS’s 2013 Preamble commentary, and document the final determination and evidence supporting a final decision. Again, because breach incidents are so fact-sensitive and require judgement, the input of an attorney or other appropriate expert should also be sought before taking any final action one way or the other. Additionally, the best “medicine” against employee snooping is providing regular and meaningful HIPAA training, including security reminders, that targets exactly these types of (unfortunately) all too-common behaviors that employees engage in because of a lack of understanding or appreciation of the boundaries for electronic PHI access when it is readily available through EMRs. Lurie Childrens’ Hospital states in its website Notice that it has since implemented organization-wide re-training of its employees in response to the recent employee incidents. However, covered entities should be proactive and not reactive in order to avoid similar types of incidents from taking place at their organization. Basic “HIPAA 101” type training is not as effective as training that targets the “Top 10” behaviors engaged in by employees that can lead to privacy and security incidents, and breaches. For training resources, subscribe to Legal HIE Member-only content here.

Like this Breach Assessment Tool? Get more awesome tools like this one, plus a detailed Breach Notification Policy & Procedure through a Member-Only Subscription you can get right here.

HHS Description & Commentary (78 Fed Reg 5642-5643 (January 25, 2013)):

- Nature and Extent of the PHI. Evaluate the nature and the extent of the PHI involved, including the types of identifiers and the likelihood of re-identification of the information. To assess this factor, entities should consider the type of PHI involved in the impermissible use or disclosure, such as whether the disclosure involved information that is of a more sensitive For example, with respect to financial information, this includes credit card numbers, social security numbers, or other information that increases the risk of identity theft or financial fraud. With respect to clinical information, this may involve considering not only the nature of the services or other information but also the amount of detailed clinical information involved (e.g., treatment plan, diagnosis, medication, medical history information, test results). Considering the type of PHI involved in the impermissible use or disclosure will help entities determine the probability that the PHI could be used by an unauthorized recipient in a manner adverse to the individual or otherwise used to further the unauthorized recipient’s own interests. Additionally, in situations where there are few, if any, direct identifiers in the information impermissibly used or disclosed, entities should determine whether there is a likelihood that the PHI released could be re-identified based on the context and the ability to link the information with other available information. For example, if an entity impermissibly disclosed a list of patient names, addresses, and hospital identification numbers, the PHI is obviously identifiable, and a risk assessment likely would determine that there is more than a low probability that the information has been compromised, dependent on an assessment of the other factors discussed below. Alternatively, if the entity disclosed a list of patient discharge dates and diagnoses, the entity would need to consider whether any of the individuals could be identified based on the specificity of the diagnosis, the size of the community served by the covered entity, or whether the unauthorized recipient of the information may have the ability to combine the information with other available information to re-identify the affected individuals (considering this factor with the 2nd factor discussed below).

- The Unauthorized Person Who Disclosed/Used the PHI. Consider who the unauthorized recipient is or might be. Ex: if the recipient person is someone at another Covered Entity or Business Associate, then this may support a finding that there is a lower probability that the PHI has been compromised since CEs and BAs are obligated to protect the privacy and security of PHI in a similar manner as the CE or BA from where the breached PHI originated. Another example given is if PHI containing dates of health care service and diagnoses of certain employees was impermissibly disclosed to their employer, the employer may be able to determine that the information pertains to specific employees based on other information available to the employer, such as dates of absence from work. In this case, there may be more than a low probability that the PHI has been compromised.

- Whether the PHI was actually Acquired or Viewed. Investigate and determine if the PHI was actually acquired or viewed or, alternatively, if only the opportunity existed for the information to be acquired or viewed. One example given is where a Covered Entity mails information to the wrong individual who opens the envelope and calls the Covered Entity to say that he/she received the information in error. In contrast, a lost or stolen laptop is recovered and a forensic analysis shows that the otherwise unencrypted PHI on the laptop was never accessed, viewed, acquired, transferred, or otherwise compromised, the Covered Entity could determine that the information was not actually acquired by an unauthorized individual even though the opportunity existed.

- Mitigation. Consider the extent to which, and what steps need to be taken to mitigate, and once taken, how effective the mitigation was. Attempt to mitigate the risks to the PHI following any impermissible use or disclosure, such as by obtaining the recipient’s satisfactory assurances that the information will not be further used or disclosed (through a Confidentiality Agreement or similar means) or will be destroyed, and should consider the extent and efficacy of the mitigation when determining the probability that the PHI has been compromised. This factor, when considered in combination with the factor regarding the unauthorized recipient of the information discussed above, may lead to different results in terms of the risk to the PHI. For example, a covered entity may be able to obtain and rely on the assurances of an employee, affiliated entity, business associate, or another covered entity that the entity or person destroyed information it received in error, while such assurances from certain third parties may not be sufficient. The recipient of the information will have an impact on whether you can conclude that an impermissible use or disclosure has been appropriately mitigated.